Anxiety

Just about any endeavor to define clinically something which exists solely in the emotional world results in not-a-definition, jargon from nether regions of psychology and sociology creating a thin, unsatisfying soup. It’s an irony, to me, since anxiety is the most common thing in the world, akin to the elixir of the gods, the most common element of the heart in the same sense water is the most common element in the natural world, and just as versatile, whose function covers every range of good and evil, both in motivation and in outcome. Anxiety is what makes the world go ’round.

Defining By Narrative

1. My best friend, Chris Thoma, when he was a senior in college, and I was a junior, said, “If you don’t ask her out, I will.” The lady in question was a freshman named Deb. A pretty, late-blooming, innocent-eyed dove from from the Upper Midwest, she had just broken up with her first boyfriend. The mass of campus males stirred at the news. I thought I had been the only one stalking her. We all shared the same problem: timing. How long should we wait before the rebound period would be over? Is the rebound boyfriend in a position of advantage or disadvantage? Does one risk the prejudicial rejection because of premature…discourse? Or does one risk the prejudicial rejection because the early bird was in advance and got the worm?

“If you don’t ask her out, then I will.” I hastily left his dorm room, where we were playing guitar and watching Beavis and Butthead together, went to the bathroom, threw up, went to my dorm room, panicked, picked up the phone, dialed the number, and asked for Barb.

“There’s no Barb here,” Deb said.

“Barb Jee-oh?” I asked, dying inside, a flop sweat making the phone slippery.

“G-I-O-E is pronounced ‘Joy,'” she said. “And my name is Deb.”

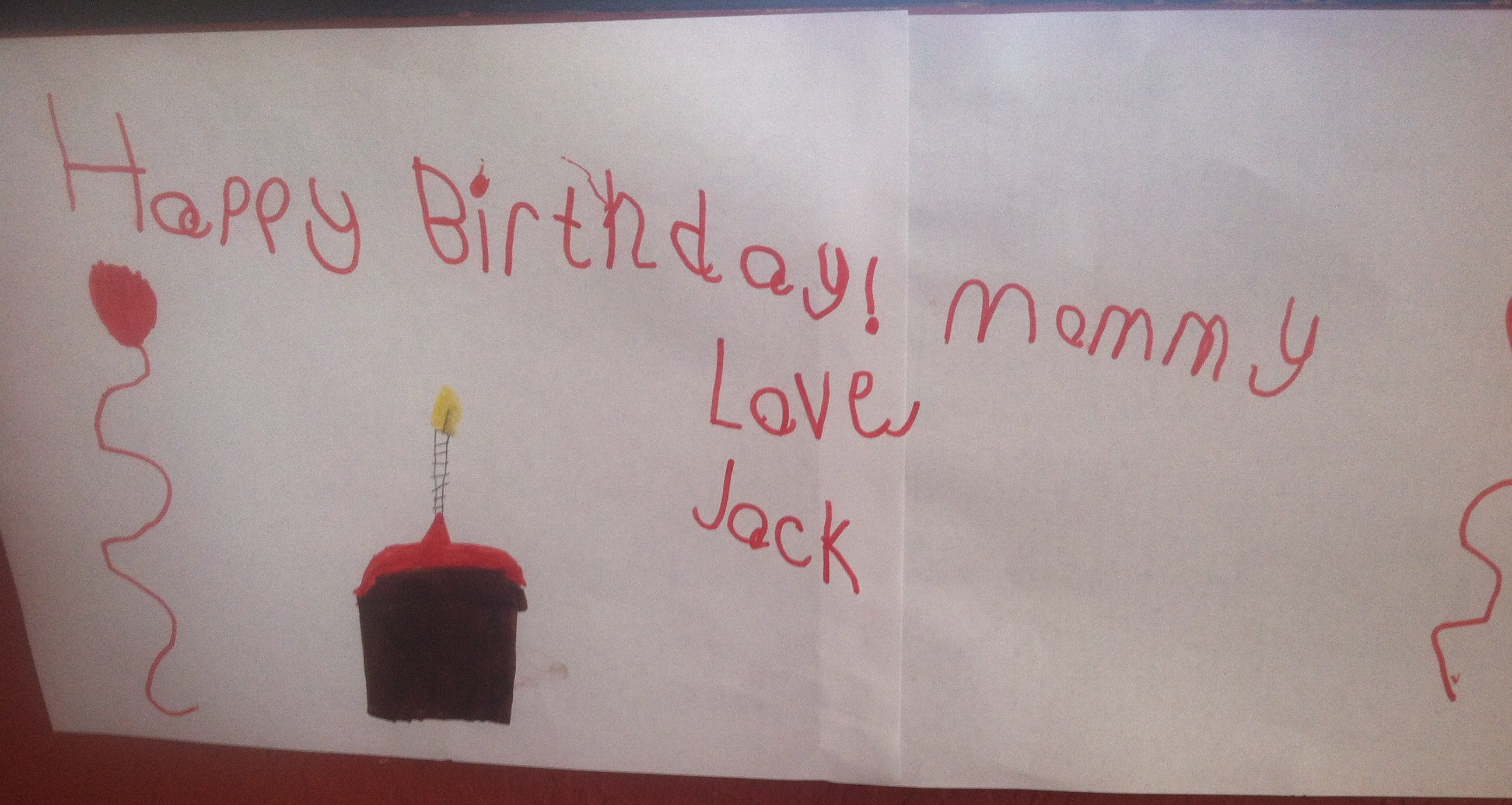

Over the summer she sent me chocolate chip cookies. In November I asked her to marry me. We have four boys and a house in Tonawanda, almost twenty-three years blissfully married.

May 2017

2. A fictionalized true story:

Blake, a middle-aged veteran of the first war in Iraq, found himself limping twenty years later from a wound he received in the war. Veterans Affairs took their time assigning him proper care, during which time his wound grew worse, which triggered a little bit of that ubiquitous post-traumatic stress, which, in turn, triggered some bad habits with alcohol and marijuana.

Marie, his middle-aged wife of many long-suffering years, was watching herself grow old in the mirror he held up to her in his eyes day-by-day, as he sat in front of the television, disabled and on disability. When he spoke, he spoke only of the pain or of those associated with the pain. In other words, he whined. The pilot light, all that was left of their passion for each other, went out.

Her maidenhood was distant in the past, but she was not willing to let it expire completely in Blake’s lap as he was unable to stand erect out of his rickety reclining easy chair. Therefore, she got herself a job in a stockroom, where she got herself a boyfriend, with whom she enjoyed life in the backseat of a car, in clandestine meetings at his apartment while his old lady was out, and at perfectly awful motels. After a time of it, she told Blake.

Blake rose from his rickety reclining easy chair, picked up a hammer, and drove to the other man’s house.

3. When I was four years old, my dad had squeezed blood from rocks and founded a Lutheran congregation in southwestern Louisiana. It was a true miracle, and (if I remember correctly) when the brick building was dedicated, there was much rejoicing. The first Christmas there would prove to be an event of which the angels themselves would sing as though Christ himself had found this place worthy instead of the stable in Bethlehem. The thing was going off with resplendent beauty which was increasing throughout every practice, in which I dutifully practiced singing “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” over the manger for weeks on end. Christmas Eve was at hand.

While still at home on that fateful Eve, I felt the anxiety rise—these forty-one years later I recall the feeling perfectly—and I expressed quite plainly that I did not desire to attend that evening’s festivities. I was convinced by the responses to my pleas that I was unheard. The pastor, you see, was preoccupied with the Big Event. And who can blame him?

In the car I began to cry, mostly to myself, being reassured by my mother that my favorite Sunday School teacher would be sure to bring me through whatever troubles may come. It was kind of my dear mother, but she had not addressed the actual problem, that is, I would be singing in front of multitudes of hordes, and with a spotlight on me!

At the door (it was dark out), I fell to the ground, whereupon my dad yanked me up by the wrist with one hand, and in a single motion with the other hand, unbuckled and slid off his belt, proceeding to belt me with it in front of the church door, God, and all the parishioners who were arriving. Thus I was cured of my anxiety.

When the time came, I stood silently with my two coeval angels and beloved Sunday School teacher, and I did not sing. My mother was delighted and told me the story for years.

This one is tricky, with anxiety all over the place. One quickly forgives my dad, a thirtysomething leader of a brand-new community born of his own sweat, especially when one remembers a) this is 1977 and b) this is the deepest Deep South there is.

He still shouldn’t have done it, but he was impelled.

Now, I use the word “impel” an awful lot to describe anxiety, the causation aspect of anxiety, and I think I’ve created an idiosyncratic use of the word. It’s a choice out of negation, to be sure: I want to avoid the idea of compulsion, which is associated with anxiety, and is also a causing-force from within, but I think compulsion brings to mind lack of control, lack of insight, lack of thought or forethought; I also mean to avoid the idea of complete externality, in which the experience of anxiety is entirely reactive to outside forces. Impel, on the other hand, with impulsion and impulsive capture the whole experience. Impulses are forces from within, yet certainly concerned with externalities, both in the reactionary sense and also proactivity.

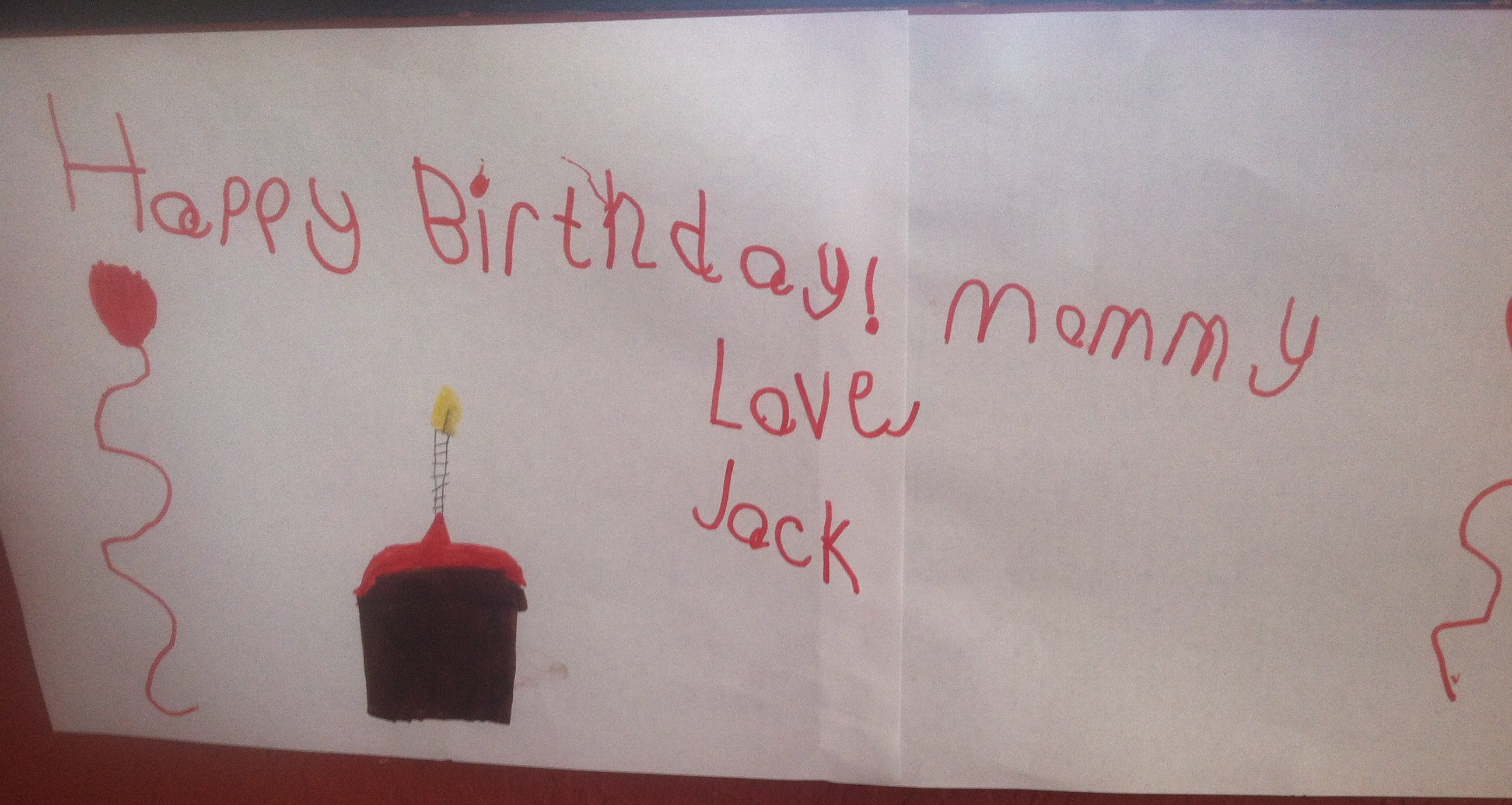

4. My oldest son shot out of the womb with an aggressive interest in electrical engineering. By the time he was four, he knew the function of every switch, knob, lever, pull-chain, rheostat, outlet, socket, and receptacle in the house. He had a habit of waking up at odd hours to delight himself unplugging all our appliances and lamps. He continually reset the water filter timer in our refrigerator. He was a menace to everything which gave light or motion. The point finally arrived where we stopped hovering over him, resigning ourselves to his inevitable electrocution, watching him with one eye while we went about something resembling a normal daily life. He did not cease plugging, unplugging, and flipping switches.

Our neighbor invited us over for a little Christmas cheer, and within minutes, the boy had grown comfortable with the new environment, and while Deb and I continued chatting amicably, keeping one eye on our li’l engineer, he unplugged a minor appliance. Our neighbor leaped from his seat. “Whoa! Whoa! Whoa!” he cried out. With a gallant effort he plucked the boy from his place near the outlet and delivered him over to Deb’s lap. “I’m not one to handle someone’s child,” he said apologetically, “but I really didn’t want him to get himself hurt.”

Deb and I smiled and explained. We all had a good laugh, but our neighbor kept a wary eye on our son.

With this irrepressible curiosity about things electrical came also some behavioral…concerns (shall we say), and we thought it would be a good idea to see a family counselor and therapist. I must admit I found the tall, heavy, darkly bearded, Jewish figure of a man rather imposing, so I blurted out, “Our son is possessed by anxiety.” I told him the story of our neighbor’s house.

“Sounds like he doesn’t have enough anxiety,” he responded. Thus began a wonderful decade with a wonderful counselor.

That kid, circa 2007, aged 4 years, will rewire your house, whether you want it or not.

5. I saw this one just today: I assumed my place in line at JoAnn Fabrics (I needed a length of tan muslin) behind a tall man of African descent in his late 20s. In front of him was an equally tall, pleasantly pretty Caucasian woman in her late 30s. In his hand was what I would describe as fabric for traditional sub-Saharan African clothing or decoration. In her basket was a wide variety of fabric. I sensed the tall man looking at my muslin. I was looking at my phone, pretending not to be observing anything, just checking my fantasy lineup for the evening.

He looked at her basket. A minute passed. Another minute passed. The line was not moving and I had to use the bathroom. The tall man cleared his throat quite gently, saying to the tall woman in a very low voice, “Excuse me, but what caused you to start sewing?” His accent was foreign, perhaps African, perhaps Caribbean. His voice drew my attention, and I looked up just in time to see her face change from morbid boredom to a broad, beautiful smile which lifted her entire countenance. That entire corner of the store suddenly brightened a bit, as if a little sunshine has escaped from his evening cradle and was lost in our midst.

“I made a New Year Resolution—I am a runner, you see, and I hurt myself, so I took up sewing my own clothes to keep myself occupied—I made a New Year Resolution to sew all my clothes this year.”

The tall man was entranced, and he asked many questions which revealed that he was about to make his first attempt at sewing his own clothing.

“Ball,” she said, at the last. “The author’s name is Ball. I checked out her sewing book from the library so many times I finally bought it.”

That should do it for a definition of anxiety.