Memes are destroying America. Haven’t you heard? Whether produced by enemy nations as psy-ops or simply by the evil among and within ourselves, they are definitely bad. And they are definitely serious.

As someone who takes rhetoric pretty seriously, I requested a review copy of a certain book by what I had been assured were two of the top scholars studying rhetoric today on the topic of memes, and specifically alt-right memes in 2015/16. I assumed the narrow focus would allow for a deep dive; I was incorrect. The book was 75% comparative communications theory, 20% summaries of news and knowyourmeme.com articles about memes, and 5% engagement with source material.

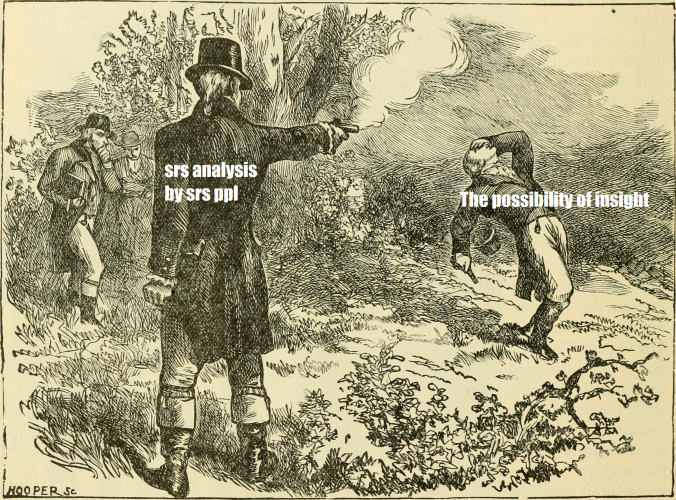

The rule of serious attempts to analyze memes as rhetoric is that such attempts are impossible to take seriously. They mutter ominously about dark motives and dire consequences (or scream about this “VIRTUALLY UNREGULATED” genre), all sound and fury, without insight whatsoever.

The combination of their newness, their frivolity, and the audience for which serious works are written, seems guaranteed to produce the most empty, pointless analysis imaginable.

What’s special about memes? Well, it’s like a third of the population became political cartoonists overnight, only the result is even less subtle than that. And of course, politics is but one area that’s been memed; everything from video games and sports to philosophy and theology have subreddits and Facebook pages aplenty dedicated to creating and sharing memes.

But that’s it, really. It’s a more participatory political cartoon. In day to day interactions online, it is less propaganda (which is what the serious analysts want it to be) than a visual stand-in for a one-liner. It’s a means for shit-talking as well as just dicking around for laughs and attention.

Other than that, its significance is no different from any other form of rhetoric. It seems significant now because it’s everywhere. But like all rhetoric, its very pervasiveness militates against a general significance. To put it differently; the literary theorist might think Coca-Cola can brainwash you with advertising, but Pepsi, and for that matter health drinks, can advertise too. A lot of rhetorical effects cancel one another out, just like my vote for a Democrat cancels out your vote for a Republican.

An Actual Serious Analysis™ would focus on specific source material from a specific period and analyze specific effects. This is what the aforementioned book should have done; just gone through hundreds and hundreds of memes and traced their proliferation and evolution, and attempt to suss out their specific impact from how they are received in particular communities. THAT would be interesting. I would find it interesting, at any rate.

Rhetoric does matter. Business-as-usual rhetorical effects occur within the comfortable confines of institutions; you following the voting procedure. The officiant declares a couple married. In as much as the typical meme or the typical political ad has an effect, it is to change people’s within-institutional choices, in this case who they vote for. But the institutions themselves only exist because, much like money, the community “understands” them to. Some rhetorical effects can thus weaken institutions, as when confidence in a currency plummets and people stop accepting it as tender altogether. Part of the buzz around memes is that people really think we’re memeing our way to institutional death. I am skeptical that the memes are the problem. But if you think, as I do, that rhetoric matters, and also that memes are a form of it, then consider bypassing the unified-theory-of-memes approach in favor of an approach that sticks close to specific examples and pays attention to the communities that make use of them.